Nothing Without Labour: Chapter 3

Thursday, November 27, 1851

James Long started making ginger bread in the shapes of animals, using confectionery pastes or currants for eyes. His diversification into other confectionery lines found a readysale. It grew to such an extent that in 1864, James Long purchased a delicensed hotel, the Golden Gate, situated on the eastern corner of East and Victoria Streets, Ballarat.

The top floor of the building was used as a dwelling, the lower floor for manufacturing.

A year earlier, James Long’s wife, Olivia died at the tender age of 24, in childbirth. Their seven-year marriage had produced five children, including the last (Olivia) named after her mother for obvious reasons. Their children were:

• William Edwin

• Harriet Caroline

• Alfred James

• Thomas Percy, and

• Olivia

Within six months, James married again. He joined with Mary Wilcock, 22, in a ceremony performed by the Rev. Mark Bradney, who officiated at the first marriage. Mary was born at Water Looe, Elland, in Yorkshire on September 7, 1842. Her parents were James Wilcock and Margaret (nee Cragg) who was the daughter of publican John Cragg and his wife Elizabeth (nee Penny).

James Long’s mother-in-law Margaret later lived with James and Mary at ‘Burswood’ in Portland (Vic.), passing on at the age of 94½.

James and Mary had eight children:

• Elizabeth Mary

• Charles Edward

• Arthur Henry

• Rowland Theophilus

• Margaret Annie

• Robert Thomas

• Sarah Frances, and

• Leslie James

James and Mary worked hard. Times were strenuous and brave hearts were needed to cope with the stresses of the time. Mary had children to care for, and at the same time she boarded some of the hands working at the factory.

She did her share, often washing the returned biscuit tins, ready to go out to stores, again full of product. James started travelling early in the morning to reach sales prospects. There were no made roads, and as his grandson Allan later recalled: “There were still blacks about, and in some areas not too friendly.

“There were tramps and swagmen who could not be trusted. Although Melbourne and Ballarat were now linked with the railway, transporting goods to such places as Wallace, Mt Egerton, Creswick, Searsdale and other places had their difficulty.

“Bridges over streams were few, and many times attempting to ford streams, the horse took fright, turning over the wagon with the result of loss.”

Times improved, and more space was needed for expansion so they moved the residence to as building two stories tall, opposite the factory. Some years later they left this building, to reside at Glen Park at the commanding ‘Longwood’.

From time-to-time the factory had additions, and land was purchased for stabling and store rooms. The new premises gave James the opportunity to p[roduce a greater variety of goods.

Long’s Cough Drops were introduced and found a ready sale in Victoria. Interstate sales were made, but became difficult because of State (inter-colony) jealousies.

Long’s Rice Biscuits proved popular with mothers rearing children. The labels on the tins included pictures of twins enjoying the virtues of Long’s biscuits. Cracknell biscuits, a very light product of corn, flour and egges, were retailed for 2/9 per pound.

Long’s Cream Crackers had a continuous public demand and were of a flaky texture of described as very light. Much of the success in the crackers was deemed to be because of the water used. It has been suggested that water from ‘Longwood’ (also known as ‘The Springs’) may have been used at the factory.

Date bars, long’s Sultana Luncheon, ‘ginger nuts, Marie shortbread, Baw Baw and creams were all in the range.

Long’s Lollies and Toffees had a big sale with the young people and in those days such confectionery was turned out in stick form. The price for a sizeable stick was one penny. At that time you could also buy 16 aniseed balls for 1/- (one shilling).

James Long’s brother, William, told of chocolates manufactured at Ballarat East, and exported for sale to New Zealand. The chocolates were to be soft-centred, however all the centres had gone rock hard by the time they arrived. A quick letter was written explaining that the buyers should hold on to the stock for another few weeks when the centres would cream.

Certain chemicals were used in the mixture which had a gradual chemical reaction resulting in a creamy texture. The preparation was called a ‘Sugar Kill’.

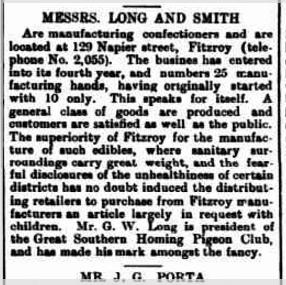

Another winner was Long’s Milk Kisses, but this product led to family squabbles that saw relatives leave Ballarat to start their own confectionery business. In 1898, local business directories show Mr George Walter Long (James’s nephew) in partnership with Mr Alf Smith in Napier St, Fitzroy.

George travelled and built up a strong country connection. The postal directories show not only offices at 78, 80 and 128 Napier Street, but also at 19 Main Street, Ballarat. Long and Smith are listed as ‘manufacturing confectioners’. By 1917, an additional office was opened at 70 High Street, Bendigo, further increasing operations.

Alf Smith attended to the books and despatch of goods up until his death in 1917. For a time George carried on the business which had now moved to larger premises in Young Street, Fitzroy.

He then joined an amalgamation with the famous A.W. Allen and also Miller Bros., the Amazon Confectionery Company, Clarke-Luke Pty Ltd, National Candy Company and Tuckett Obinson Pty Ltd.

The new Melbourne-based conglomerate commenced operations on September 1, 1917, with G.W. Long joining the foundation board of eight members.

A.W. Allen’s first factory was in Kensington, followed by construction of the new plant on Riverside Avenue, overlooking the Yarra.

Another product that James Long turned out had an unfortunate ending. “Mr Honey Barnes, as he was always referred to in the Long family, was responsible for the packing and blending of honey.

Honey from different architects had different flavour and colouring, and had to be blended one with the other to obtain aroma and the desired degree of colouring.

Something happened between James Long and “Honey Barnes”. Barnes left and started business in Burnley. Barnes honey is still packed and marketed in shops today.

The factory’s biscuit ovens were of brick, and fired and heated by timber logs, some six feet long. In the morning, ashes and spent materials were removed, and cleaned, ready for baking. Hundreds of tons of timber had to be purchased.

Forty square feet constituted a ton, and if the timber was not packed properly then one would be paying for wood that was not there. James Long never neglected this inspection.

When he retired to Portland, and bought up wood for the winter fires, he was still cautious. He would measure up and calculate, and then get his grandson Allan, to check over – never telling his calculations until proved. Coke was also bought for the confectionery baking. It offered a constant heat and is free from smoke and ashes.

Another product was jam. Evidently this venture was not a success. The method of making jams in the late 1800s was very much different to that used today. First, a ‘pulp’ was prepared and stored in four gallon tins, after which sugar and other required fruits were added as the market demanded.

In the end, wagon-loads of ‘pulp’ were sent out to ‘Longwood’ to be spread on the paddock soil, and then ploughed in to be fertiliser. James Long wasted nothing! Biscuit waste was sent to feed the pigs, geese, ducks, turkeys and hens.

James was awarded a gold medal for his biscuits at one of the big exhibitions. Part of his success was in his skills of buying and selling. Before the days of Australia producing its own sugar cane, some was imported from Fiji. James would come down to Melbourne and buy an entire shipload of sugar.

Sometimes sea water would damage some of the cargo. He would have to perform quick calculations on how much could be sold through retail markets, and how much could be used for biscuits where salt was required.

Labor Omnia Vincit, popularised as ‘Nothing Without Labour’, but strictly ‘Labor Conquers Everything’.

Calculations would also encompass that needed for confectionery. James would bargain in fractions of farthings with the period of settling.

Difficulties in trading from Ballarat presented problems. It was always cheaper for country folk to rail goods from Melbourne than get them from Ballarat, although closer. The Sunshine Harvester Company, which started in Ballarat, had to shift closer to Melbourne to overcome those difficulties. Hence, the modern day City of Sunshine.

To overcome his own difficulties, James procured a depot in Melbourne, to where he would ship goods in bulk, then re-rail them to the customer’s destination. He had his own stationery and cheques printed with his heraldic crest, bearing the Latin: “Labor Omnia Vincit” popularised as “Nothing Without Labor”, but strictly translated is “Labour Conquers Everything”.

He was keen. In his early life he was a drinker, and turned a strict teetotaller, apparently after making a fool of himself at a funeral. He recalled that giving up drink he “fought every devil that was”. James had a very quick temper, and when roused would declare “Jumping Moses”. He soon returned to calm.

He was right in repeating” “Nothing Without Labour”.