Nothing Without Labour: Chapter 4

Thursday, November 27, 1851

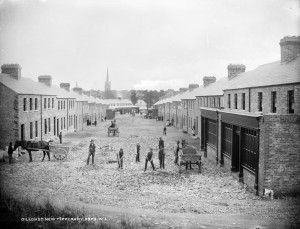

By 1874 James Long was a well-known identity in Ballarat East, and through his interest in the community he was approached to stand for local government, to which he was elected.

The following year he became Mayor, serving two more terms in 1877-78 and 1878-79.

It is recorded that while officiating: “The business of the Council was transacted in a thoroughly capable, efficient and expeditious manner, Mayor Long ruling in a way which invariably gave satisfaction to his brother Councillors.”

It was felt that the presence of James Long on the magisterial bench would be a desirable thing, and in 1876, the Governor-in-Council informed him of his appointment as a Justice of the Peace.

It was reported of him: “Whenever this gentleman has taken his seat on the bench he has always given due attention and consideration to cases upon which he was called to adjudicate.” Ballarat East municipality was described in the 1878 Municipal Directory as having 3475 ratepayers and 92 publicans.

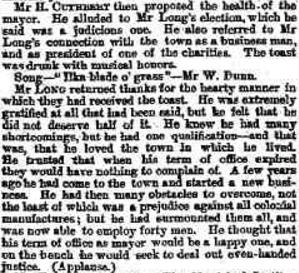

The Ballarat Courier on August 27, 1875 reported the Mayoral Dinner organised in honour of James Long.

• Mr H. Cuthbert then proposed the health of the Mayor. He alluded to Mr Long’s election which he said was a judicious one.

• He also referred to Mr Long’s connection with the town as a businessman, and as President of one of the charities.

• The toast was drunk with musical honours.

• Lika Blade O’grass – Mr W. Dunn.

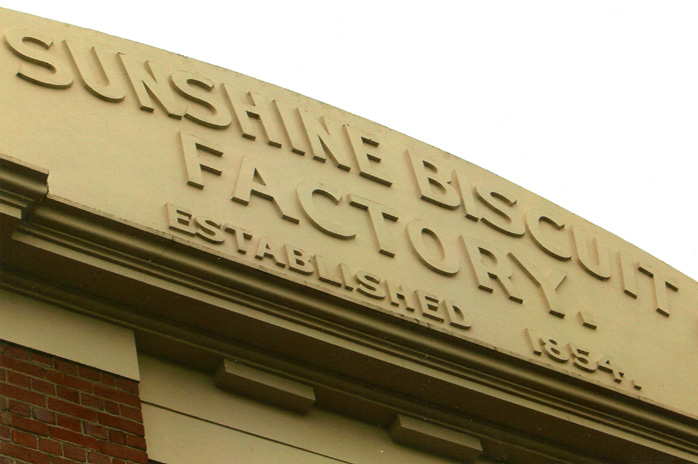

James Long returned thanks for the hearty manner in which they had received the toast. A few years ago he had come to the town and started a new business. He had many obstacles to overcome, not the least of which was a prejudice against all colonial manufacturers; he had surmounted them all, and was now able to employ 40 men.

He had thought that his term of office as Mayor would be a happy one, and on the bench he would seek to deal out even-handed justice. (Applause)

James’s son, Thomas, wrote of a visit to Ballarat East by the Governor: “I remember the time the Governor was to visit our City: what a stir it created in our home. His Lordship, the Mayor, had to have his coat specially pressed and cleaned. His boots received an extra polish, and his top hat, my word it did shine.

“To see Dad in a carriage drawn by a pair of grey horses and a man in livery, with the Governor sitting at his side in the grand parade. Don’t I remember the stir that took place in our home when the Premier Sir Graham Berry accepted the invitation of the Mayor to be his guest during his official visit to our City. They were great days.”

James’s new home was ‘Longwood’, derived from Napoleon Bonaparte’s home on the Atlantic island of St Helena. Donaparte’s home took its name from the Longwood Plains in the north-east of the island.

James obviously thought it was an appropriate name, seeing his own name was ‘Long’, and with the amount of wood on the property. The property between the hills and valleys was some six kilometres east of Ballarat at Glen Park. It sees the Gong Gong Reservoir on one side and the Swan on the other, supplying Ballarat with water.

The property was also known locally as ‘The Springs’ as there were springs on the land, similar to those at Daylesford.

‘Longwood’ was a big building with large rooms, having a long passage from front to back. The verandahs nearly covered the four outside walls. The gardens were spacious with a fountain in front of the house.

Carriageways led to both front and back entrances, and were covered with white quartz. Close to the house was a duck pond with willow tress around the border. Also in the pond were goldfish. James once caught grandson Allan and his young cousin Vernon with a piece of string and bent pin for a hook, trying to catch fish. James gave them weeding jobs as punishment.

There were two other ponds – one connected with underground pipes to the fountain, and the other dam was for watering the cattle. The back garden and orchard was laid out in squares with apples, pears, cherries, mulberry, plums and apricots.

A summer house graced the garden. It was covered in ivy and a retreat for James’s mother-in-law, Mrs Wilcock.

Longwood’s boundary had pine trees. The property continued to stand but with some of the rooms taken down, ceilings lowered and the fountain long destroyed by cattle. A letter to Alan Charles Long, who researched this material, from Mr Scott Douglas in 1974, said Longwood then had eight rooms: “The road is still called Long’s Hill.”

Difficulties in trading In Victoria prior to Federation was encountered. Between 1880 and 1890 there was a mad rush from London to lend money to Victoria, particularly for railway construction throughout the colony.

Buildings for public purposes were going up even before the times warranted their use. Private homes were also being built, but their cost was relatively higher. This borrowed money had the results of forcing up the cost of living, and those on lower incomes formed unions to protest.

Despite the difficulties Mr and Mrs James Long were able to pay a visit to their respective home lands in 1889: James to Tipperary, and Mary to Yorkshire.

James was agreeably surprised to find that on this voyage on The Brittanica he was able to renew his acquaintance with the doctor who sailed with him out to Australia in 1851. They enjoyed the visit, with happy reunions with relatives and friends.

We have already referred to James’s impatient nature and his wife later recounted this story. James had arranged for a boatman to row he and Mary to the other side of Lake Killarney with instructions to be back at a certain time. The boatman failed to return at the appointed time, and James was furious.

When he finally arrived, James reprimanded him in no uncertain terms, evidently arousing another Irish temper: “Look here boss,” pointed out the boatman. “You might be born to rule the world, but you’re not going to rule me. As far as I am concerned you can find your own way back.” Evidently, this was one occasion when James Long did not get his own way.

When James Long arrived back in Australia, business was not as he left it. The London lenders were not keen on further advances, exports had gone down, and property values were depreciating.

Sir Francis Baring (left), with brother John Baring and son-in-law Charles Wall, in a painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence

James Long was concerned, and when cheques were presented, he had them transferred into sovereigns as soon as possible. He bought property on each side of Victoria Street, close to the factory, as the opportunities arose.

In 1890, Barings Bank in London failed, which made the Australian banks cautious. Several banks closed for a week to prevent a run on cash. In March, 1892, one bank failed, followed by another in January, 1893. In April and May, 13 banks closed their doors. James lost £30. Whatever he had, had been utilised in buying property. Her argued that these properties could not get much lower in value, and if anything they should firm.

He now had houses but could not rent them.Distress and unemployment was everywhere, so he had to select good caretakers. Gradually, conditions improved and the property values were restored.

Some years later in the early 1900s, James received a cheque for £30, with a letter explaining that this was the amount owing to him when the bank closed in 1893.

The distress caused to families concerned him. As a Justice-of-the-Peace (JP), he was able to help many of these people. He had very little time for the pawn broker. He was interested in community organisations and was involved with the public hospital, the benevolent asylum and the orphanage.

He was connected with the Barkley Street Methodist Church in Ballarat, and also attracted to the Glen Park Methodist Church. It is believed that he may have paid for the building of this church. Families linked with the establishment of this church were the Longs, Rumlers, Ralstons, Kneeshaws, Peterkins, Goldsmiths, Clarkes, Copleys, Speeds, Shaws, Ratrays, Chaseys and Welsh families. The Glen Park Methodist Church was moved to a site opposite the school (where the CFA shed is today) in 1906. (The Gong Gong Methodist Church was closed at about the same time. There was a building previously on this site which was used as a Sunday school but its origins are unknown.)

James was a great lover of music and saw that his children was taught; two of them (Sarah Frances and Lesley James) competed in the well-known South Street competitions. He had a great aversionto dancing, and objected strongly to cards being played in his home, calling them “the device of the devil”.